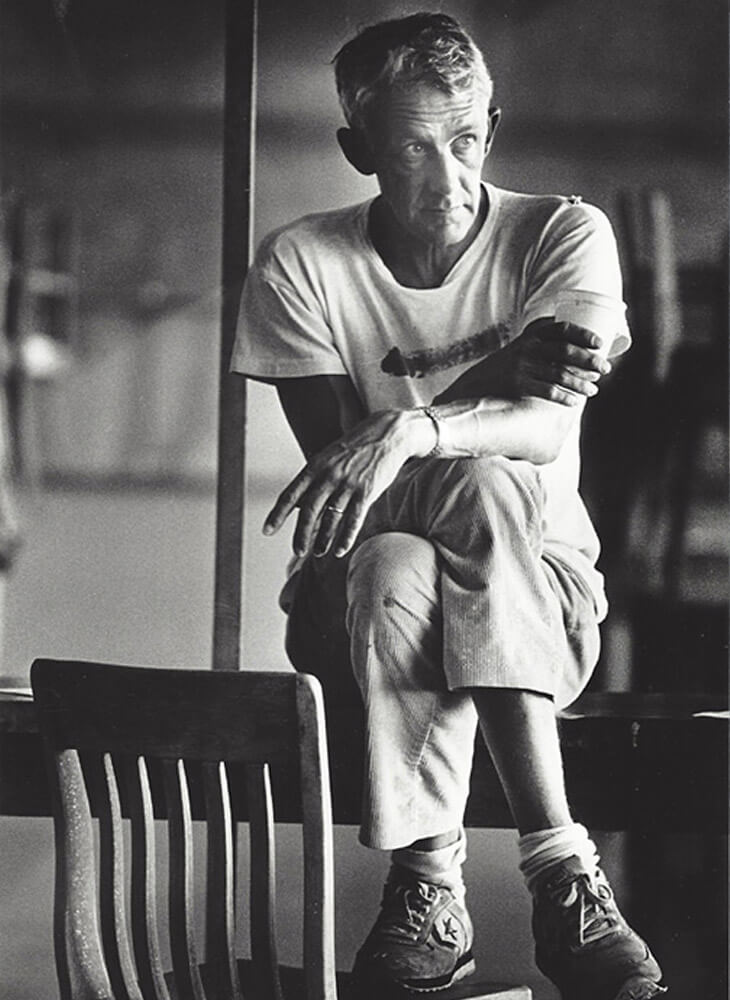

By the time Class Day rolled around, Dick Erickson was saying “this is the culmination of an incredible amount of work. Now all we’ve got to do is get the right guys in there who won’t be intimidated by the crimson shirts and the California blue at the starting line in San Diego.” Since this was a very deep team, it was unlikely he had too much trouble finding those athletes out of this group.

California had a new coach in Tim Hodges, and although highly successful as frosh coach, as a varsity coach he was an unknown. Meanwhile in Seattle, varsity oar Ty Graham got the chicken pox and stayed home… but that would only be the beginning: Jim Snody then showed up with the same highly contagious virus on race day, and now Erickson was scrambling. But his makeshift varsity won their heat handily, and in the finals rowed away from the pack with a low stroke rate and a disciplined race plan – “nothing fancy” said Erickson – defeating California by three seconds, followed by Navy, Princeton, and a way back Harvard and Yale. The JV’s also won, outclassing their nearest competitor, Harvard, by open water. “The strength of our squad showed here,” said Erickson. For a race this early in the season he noted, “I’ve not seen a varsity and a JV that rowed under such poised control.”

On April 29th, the team traveled south for the Dual on the Estuary. The freshmen, in their first serious trial of the season, were defeated by six seconds by the Bears. But the JV’s racked up a thirteen second victory, followed by a ten second win in the varsity race, the crews rowing away from Cal with each stroke in the last 800 meters in a powerful display. “Our crews are for real” said a surprised Dick Erickson. “They probably race better than they practice, which irritates me” said Erickson after watching the dominant performances of his varsity team at Cal.

Opening Day a week later was mostly for show, although the JV’s, loaded with seniors, finished their event with a faster time than the varsity in theirs. Not unlike the crews of the thirties, forties and fifties under Al Ulbrickson, this squad was deep enough to race head to head all season long, a real advantage for Erickson and competitive training.

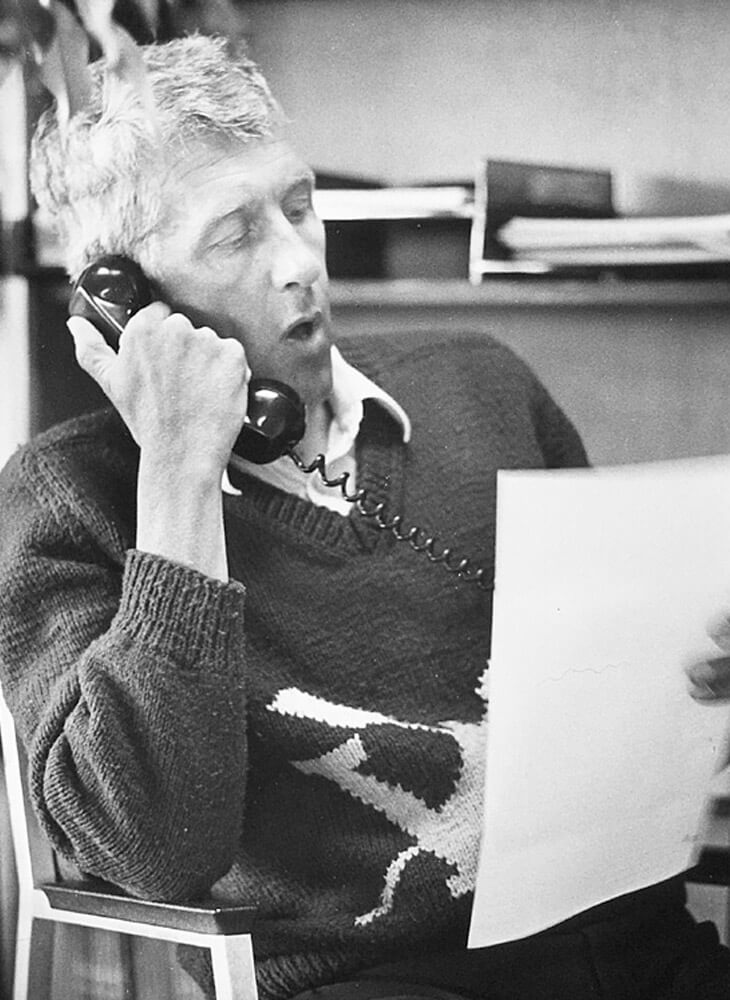

The Pac-10s moved to Lake Natoma at Sacramento in 1984, breaking the five-year hold of Redwood Shores on the event. In addition, the race format changed in two ways; one, the races were no longer dual format, instead six across: two, the top three places in the “Pac-10’s” (held on Saturday) would now race against the top three qualifiers from the “Western Sprints” (non-Pac-10 schools, also held Saturday) for the West Coast championship on Sunday. Supposedly, the winner of the Sunday varsity event would go to Cincinnati, although that was not consistent with previous years when the Pac-10 champion went, and the new format was about as clear as mud prior to the team’s arrival. The upshot was a race outline that created two chances for Washington foes to try to knock them out, prompting a bewildered but confident (and now accustomed to such last-minute machinations on the west coast) Erickson to say, “We’re ready. We’ll do whatever you want us to do.”

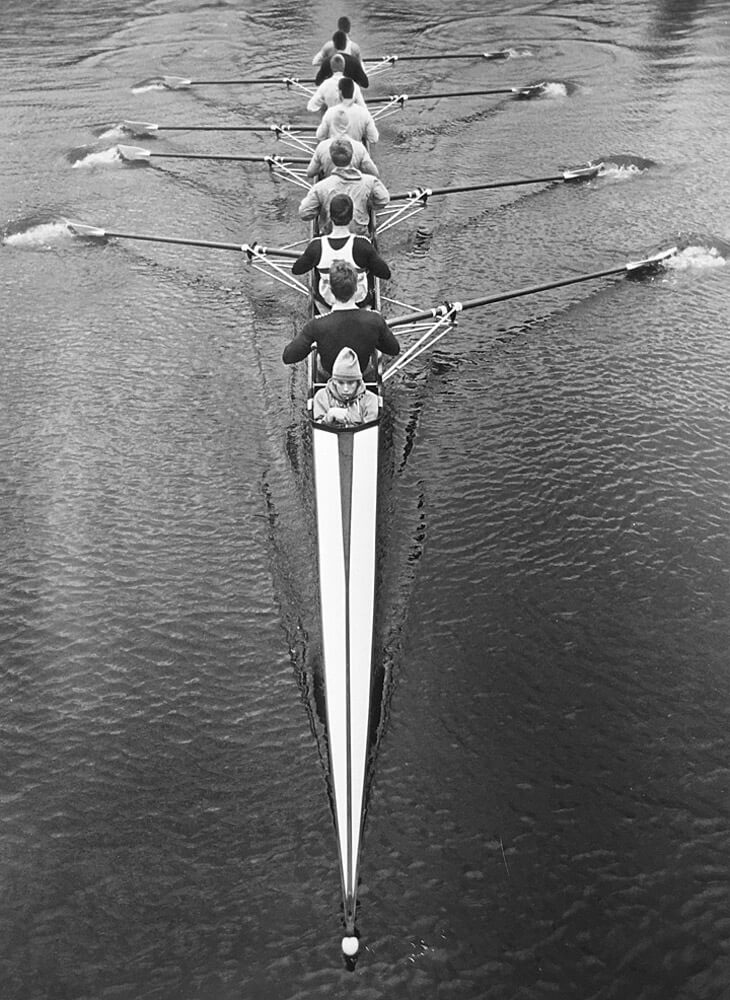

On Saturday, Washington won Pac-10 championships in the JV, lightweight varsity, and varsity events in solid fashion, all by open water. In fact the varsity race was almost sublime, a fierce yet controlled effort that varsity coxswain Mike Teather described as “a beautiful race – the best we’ve ever rowed”, the team finishing in 5:52, rowing in 95 degree heat and a light headwind.

On Sunday the team had to go out and prove it again, the varsity rowing another almost perfect race, this time winning by an even wider margin over Cal, even though Cal was close with 500 meters left. The lightweights won as well, but this time fighting off a strong bid by San Diego State to win by a deck. The JV’s also won convincingly, and Erickson was glowing about the gritty and professional way his team performed. “They not only won, but they won big. It’s been a long time since we’ve won races by that much,” said the coach.

To prepare for the Midwest weather, the team came home and spent time rowing ergometers in the locker room, where Erickson had the showers running on hot to replicate the heat and humidity on Lake Harsha. In between pieces, the guys would spend time in the drying room, a special room filled with heated air to dry the clothes of the men during the winter and spring.

But Cincinnati on June 16th was almost an anti-climax, with Brown, the winner of the Eastern Sprints, dropping out due to two of their men heading for the Olympic trials, and Rick Clothier’s tough Navy varsity, winners of the IRA regatta, unable to participate as members of that crew were headed for duty (Clothier made every effort to delay assignments to no avail). Only Yale – fifth at the Eastern Sprints, but as winners of the Harvard/Yale race invited – were able to make it, setting the National Championship up as a Dual race: Washington vs. Yale. Washington jumped to an early lead after a solid start, up by a half length 250 meters in, and powered away to lead by a length at 1000 meters. Not forgetting their experience in 1983, the crew stayed focused in the last 500 meters to win the Herschede Trophy and the free airfare to Henley that came with it. “It’s just a big relief that it’s over,” said Erickson.

The crew then came back home, only to depart a few days later with their JV teammates and two spares for Europe. Their first race, on June 24th in Amsterdam, Holland, would be against Dynamo Club of Moscow, a composite Russian club crew made up of collegiate and elite oarsmen. The Huskies, rowing in a borrowed wooden craft and rocked by jet lag and a frantic schedule, could not match the speed of the Russians, defeating the remaining Dutch crews in the race but falling to the Russians by over a length. “We should have paced ourselves better” said coxswain Mike Teather. In a follow up race two days later, the margin of defeat was about the same, but the crew rowed a much stronger body of the race (after a poor start), prompting Pat Gleason to say “we know the Russians have one of the fastest crews in the world. It built our confidence a lot to do as well as we did against them. Now, when we face the British National Team at Henley, we’ll have confidence all the way down the course.”

Once at Henley the crew was unhappy with the Carbocraft they were rowing, Erickson finally landing an Empacher after the Thursday races, the coach “waving money” (and throwing in some highly coveted Dreissigacker oars) at the first crew to lose who rowed one of these coveted crafts. “This will remove all the excuses about why we can’t compete out there, ” said the coach.

Meanwhile, after advancing two rounds into the Ladies’ Plate, the JV’s faced a Brown team made up of varsity and JV oarsmen. The crew got a good start and led through the mile mark up by three-quarters of a length, but Brown was able to move through them on the sprint and won by two-thirds of a boat length, setting a record for the event in 6:23 on the swift and wind-aided Henley course.

The varsity, now clicking in the Empacher, defeated the Danish national lightweight team, Bagsvaerd – Kvik in a tougher than expected semi-final. Later, in the other semi-final of the Grand, the British National Team (Leander and London) easily defeated Penn, setting a course record in that event (6:10) on the speedy course.

The men were confident for their last race on Sunday, but the Grand Challenge final would end the talk of an upset early, with Leander getting a one length lead by the Barrier and extending it to two and a half at the midway point. The crews stayed within about that margin the rest of the course, Leander rowing a 6:22 in more Henley-like conditions. Still, the British “rowed like a machine” said Yuri Zaplatel, an assistant to Erickson and veteran of European rowing, saying, “we lost to a better crew.” Always tough to go out on a loss, it may have been magnified given the confidence and swagger of these Huskies to lose by that margin.

That summer, rounding out the year for Washington rowing, Don Scales rowed in the U.S. lightweight 8+, and six former Huskies competed at the Olympics in Los Angeles. Bruce Beall rowed in the U.S. quad, Ed Ives and John Stillings won silver in the 4+, Al Forney won a silver in the 4-, and Charlie Clapp won a silver in the U.S. eight while Blair Horn won a gold for Canada in the same event. “As far as the men go, I think it is an indication of the kind of training we got at Washington under Dick Erickson,” Stillings, UW coxswain from 1975-78, said. “You just didn’t make the team – you were taught a lot of self-reliance. I know I appreciate him a lot more now than I did when I was rowing for him.”