The 1907 season was the first for coach Hiram Conibear and also the first year that the team would row in eight-oared shells. Conibear, a trainer by trade, knew that conditioning would be critical to the success of his eight-oared teams, particularly now that the races would be four mile events – more than twice the distance of the one and a half mile fours race.

Without a launch to follow the crews, Conibear would stand on the shore and shout directions as the crew rowed by. The “colorful” language he used was not appreciated by homeowners near the lake, and complaints were registered with the University.

But not everyone was alienated. Through the generous donations – or “voluntary funds” as Conibear called them – of the Seattle business community, the program was able to purchase from Cornell two eight-oared shells. The shells were delivered by railcar, along with three shells destined for the University of California that arrived there three days later. The west coast would now see eight-oared racing for the first time, in an annual race that would become known as the Triangular Regatta, between Washington, California, and Stanford.

Unfortunately, what the west coast would see in the first Triangular eight-oared event would be a water fight on San Francisco Bay. The course was two and a half miles on what was deemed a neutral course – Richardson Bay near Sausalito, i.e. San Francisco Bay – on a spring day. The day of the race, April 27th, the wind was blowing hard from the northwest and the Bay was awash with whitecaps.

The premature cannon boom sounding the start of the race, while Washington was backing and Stanford was virtually perpendicular to the course, was only a precursor to what was to come. Although California got off ahead, the other crews quickly caught her. As the teams continued down the course, it was impossible to keep the water out. Slowly the boats were sinking, as wave after wave washed over the gunnels, and the athletes were soaked. Finally, an already third place California went down. Although further down the course, Stanford also swamped and then, finally, leading the race and struggling to stay afloat with only about a half mile to go, the Washington shell dove into the water, submerged to the oarlocks. The race was over.

The S.S. City of Puebla, the steamship Washington had taken to California, quickly gathered the men from the water. Surprisingly, however, the ship’s crew also brought the shell up, and as all were left wondering about a re-row, the steamship set off back home for Seattle. She had already postponed her sailing for the crew race and the captain was not delaying the departure further.

The following Monday morning, under much better conditions, Stanford and California raced with the understanding that the winner would go to Seattle to race Washington for the west coast championship. Stanford went on to win by six lengths.

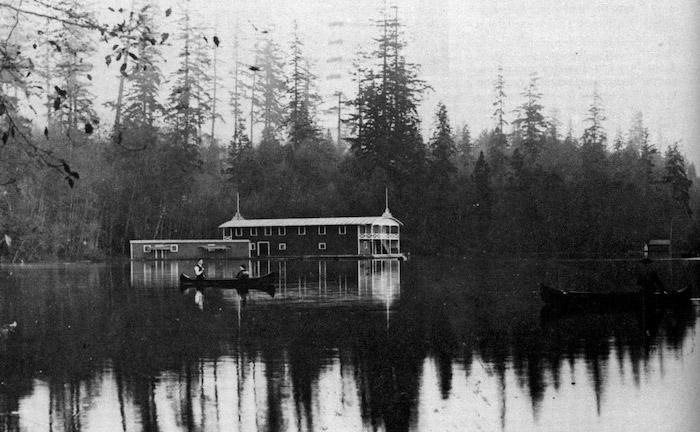

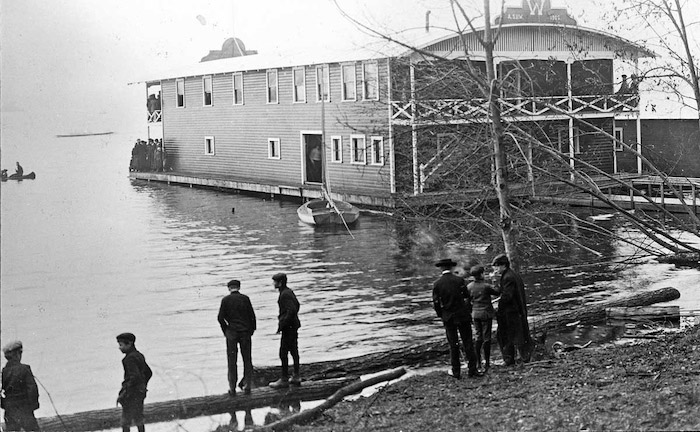

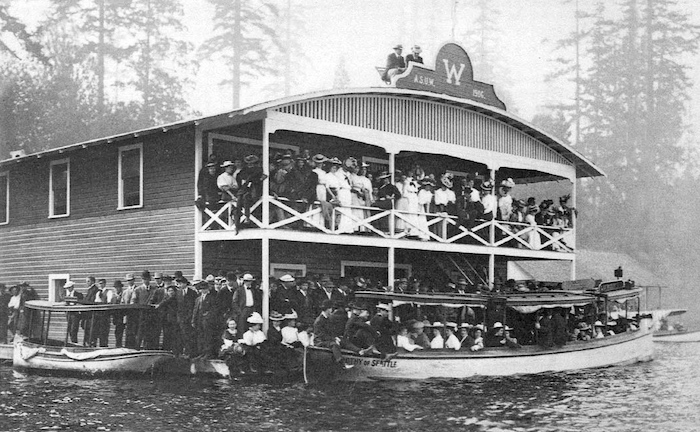

A few weeks later, amid the now traditional Seattle flotilla of watercraft and the crowds (estimated at 20,000 people) lining the four mile, Leschi to Laurelhurst Point course, the championship went out under excellent conditions on June 2nd. Included on one of the ships was “A party of special interest and importance… consisting of Gov. Albert E. Mead and party, Adj. Gen. James A. Drain and a large representation from the fifty prominent businessmen of the city who were the recent donors to the University of Washington of the shell in the race.” (1)

Following a spirited start, Washington gradually moved ahead while under stroking her competitor, a sign that Conibear’s conditioning program had paid off. The crew crossed the finish line about three lengths ahead of Stanford in 23:38, and were crowned champions of the west before a jubilant Seattle crowd.

An elated Conibear said after the race: “In my mind, Stanford did not have a single man on her crew who can pull an oar with Paul Jarvis, Hart Willis, or Homer Kirby. My rowing motto is not a new one in figuring up the essential winning qualities: ‘Hard work first; ability, second, and genius, third.” (1)

A season that had started out so dubiously had ended with the biggest win in the history of the program, and would set the stage for Conibear to take his teams to new heights.