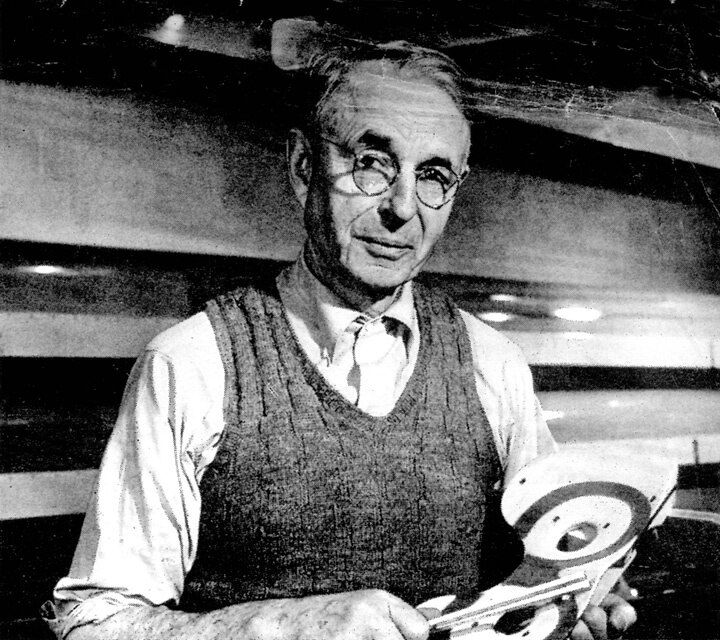

Beginning in the late fifties, there had been rumblings from upper campus about the Pocock shop at the shellhouse. A private company on public property, the University was growing increasingly uncomfortable with this arrangement, and other private enterprises, on campus. Although Curly Harris had again stepped in on behalf of the team, he could only postpone the inevitable, and by 1962 the order had come down that the Pococks would need to move. For the crew and the Pocock family, and particularly George, this would be painful; for fifty years this man, inextricably linked to Washington Rowing, had been building shells next to the young men that would row them. There is the sense that both drew inspiration from the other; that indefinable synergy, built between the Pocock shop and the life of the crewhouse, disappeared once the shop was empty.

Postponed for another year, by December of 1963 the Pococks would move to a converted warehouse on the north shore of Lake Union, directly below the I-5 bridge. A good-sized shop on the water, shells could be launched carefully from the adjacent park. It was, given the circumstances, a good solution to an unfortunate event that underscored the changes taking place on campus and in intercollegiate athletics. But on the bright side, certainly George would have agreed it beat the (sometimes) floating shop in the middle of Coal Harbor in 1911!

Being an Olympic year, the collegiate rowing community agreed that all races, throughout the season, would be at the 2000-meter distance. This allowed teams to focus all training on the increasingly popular sprint race, greatly reducing the chaotic week-to-week sprint to distance training scramble of previous years.

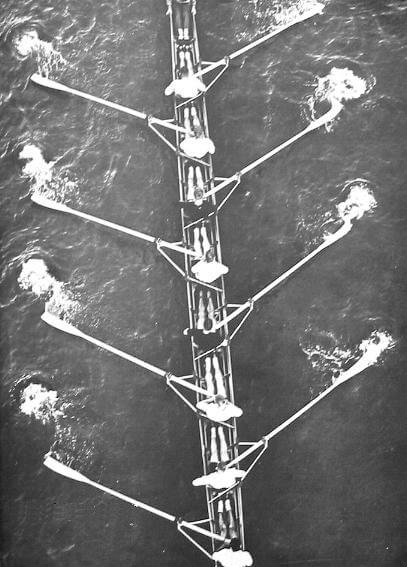

Leanderson had a deep and experienced squad returning this year and, after success at some early season racing, the team left for the Dual on the Estuary in May. The JV’s and freshmen both stroked to victory, but the varsity was defeated by a resurgent Cal squad implementing a high-stroke rate strategy, never dropping below a thirty-eight over the 2000 meter distance. This was the first Cal Dual rowed at 2000 meters, and clearly the Bear’s strategy paid off, winning by almost a length of open water.

But only weeks later, the Western Sprints saw a very different Washington varsity. Leanderson moved five men from the JV into the varsity boat, and it showed. This time the varsity, although on the losing end, came within a half-length of the Bears. The JV’s did not suffer from the change either, cruising to a half-length win even after blowing into a buoy mid-race. The freshmen were not represented. In a harbinger of things to come, the Western Sprints were held on a typically wind-blown Mission Bay course in San Diego – the first rowing event of that scale in San Diego and welcomed by an enthusiastic crowd.

On to the IRA June 19th and 20th, where for the first time the regatta would hold heats and qualify crews into a six boat final. All three Husky crews advanced to the finals, where the freshmen would finish fourth. “We didn’t have any shipwrecks on the boat… we died in the last 500 meters” croaked a disappointed first year freshmen coach, Dick Erickson.

California, still rowing the high, shorter strokes that had led them to victory on the coast, won the varsity event, with Washington finishing one and a half lengths behind in second. The Washington JV’s, unseeded in their event (i.e. underdogs), powered to an early lead and were never headed to win the Kennedy Cup for the first time since 1956. By virtue of these performances and the fourth place finish of the freshmen, Fil Leanderson took home the IRA Ten Eyck trophy for the second time in his career.

The Olympic trials were held at Pelham NY on the Orchard Beach Lagoon, and the varsity, as runner-up at the IRA, would be considered a strong contender. But although advancing into a semi-final, the crew finished behind California and Yale to be eliminated. Cal, considered the favorite going in, was subsequently defeated by the Vesper Boat Club and Harvard in the final (Yale finished fourth), Vesper winning the right to go to the Olympics. On an October night in Tokyo, this experienced crew would win the gold medal over the famed German Ratzeburg Club. Jamco Times has a reproduction and more information on this race at: JAMCO 1964 Olympic M8+ Finals.

1964 is a representative year of the rapid changes taking place in rowing during this time. Karl Adams, the physics teacher and coach of Ratzeburg, had been experimenting for a decade in various rowing styles and strategies, implementing harder, cross-training regimens, bucket (i.e. asymmetrical) rigging, and advocating higher stroked races for the 2000-meter distance, winning the 1960 Olympics and stunning the rowing world. By 1964, Harry Parker at Harvard in particular, and now California – and to a degree Washington – had adopted some of these techniques, witnessed by the “high and hard” strategy of the Cal crew at the IRA. As important were the technological changes; this would be the first year that California, following the Harry Parker lead (originally used by the Germans), used tulip blades (or “scoops”) in place of the traditional Pocock sweeps. (1) Pocock would begin developing similar oars to replace sweep blades in the months to come.

All four crews in the final of the ’64 trials were using scoops, and Vesper was rowing an Italian (Donoratico) shell. Harry Parker was ordering Stampfli Shells from Europe. The Pocock dynasty and design was beginning to see a new, albeit small, part of the market turning to re-engineered, experimental equipment. Some of it worked, some of it (like an aluminum boat) did not. But it was happening.

And then there was the shift to club crew racing at the trials. LWRC once again would enter and win the straight four trial in 1964 (bronze at the Olympics – no Washington grads). The victorious Vesper eight was a strong crew filled with elite oarsmen from around the country, and included a 46 year-old, three-time Hungarian Olympian defector as coxswain, a stroke from Cornell, a couple of Yale men, the Amlong brothers (a championship caliber pair with twelve years experience), and a 35 year-old father of six – with nineteen years of rowing behind him. Deep and experienced, and stroking with the same precision and style of Ratzeburg, this crew was as polished as they come. “This will be the end of college eights from America in the Olympics” predicted MIT coach Jack Frailey (2). Although one Olympics off in his prediction, the writing was on the wall, and he, and everyone else there, knew it.