Al Ulbrickson had a whole summer on Orcas to study his options for 1958. It was clear that neither the NCAA nor the IRA had any intention of lifting the sanctions on Washington. He had felt since the 1956 JV victory that his crews were on the upswing, but the frustrations of that season paled in comparison to having a dominant squad in ’57 that was, in his mind, so unjustly punished. An alternative was not just required, but demanded.

It is unclear when the first whispers of a trip to Henley emerged, but by the winter the Stewards and Ulbrickson had agreed that if the varsity was worthy (i.e. undefeated), they should be sent to England. No Washington crew had ever raced at the Henley Regatta (the ’48 four won the Olympics at Henley but not as part of the Henley Regatta), and “On To Henley” became the rallying cry of the entire team.

In May the crew traveled south to meet the Bears on the Estuary for their first test. The freshmen and JV’s won handily, with the varsity cruising to an almost three length win to complete the third sweep in as many years. Stanford subsequently came north and, along with a visiting UBC squad, were defeated in record times (wind aided) by all three Washington crews over the Seward Park course. The varsity won in 14:07.1, and the JV’s in 14:15.5 in their respective three-mile races.

The final race of the year came on May 31, with Washington facing UBC at the 2000 meter sprint distance, along with OSU. Cruising down the Montlake Cut, Washington prevailed by a length over UBC, with OSU losing their stroke to a catapult-like crab in the final sprint. That win sealed the deal for the varsity: they would go to Henley.

The Stewards organized a classic “On To Henley” fund drive, similar to the first IRA drives set up by Hiram Conibear, and raised more than enough to send the varsity. The Seattle community, equally frustrated with the sanctions heaped on the team, were generous in their gifts and eager to see the team compete overseas. It was also about this time that it was becoming known that the Leningrad Trud Club – the Soviets – would be racing at Henley as well; in a behind the scenes negotiation, the U.S. State Department began working with State of Washington, University, and Soviet administrations to broker a post-Henley, “people to people” race in Moscow.

The deal done, the invitation to race in Moscow came after the crew was already at Henley. It was a good thing too, since morale was not high among the men. The weather was awful; it was constantly pouring, and the day before the draw the grounds men had pumped 10,000 gallons of water from the participant’s tents. It was cold and windy and wet, and some of the men had colds. Even so, Ulbrickson said “the crew is in good shape physically.” Coxswain John Bissett quipped “You can say we are ready.”

“Thunder and lightning signified the clash of the giants in the first round of the Grand” noted The London Times rowing reporter. (1) Maybe so, but this race was over in a hurry, with the strong Soviet crew blowing out of the gates to get a three-quarter length lead by the quarter mile, and lengthening to, in Henley terms, a virtually insurmountable one length lead by the half mile. The Russians then cruised down the thin course gradually drawing out to an open water win. “We’ve rowed in worse weather than this” said Ulbrickson. “We simply never got relaxed and swinging. The boys were too tense. They wanted it too much. They were trying too hard”. (2)

The Russians, never challenged in two subsequent races, went on to win the Grand by two and a half lengths. After digesting the loss, the men began to focus on the trip to Moscow, and after a few more days of training on the Thames, flew east. The Swiftsure, the team’s shell, was flown to Helsinki, then taken aboard a Soviet train to Moscow.

Once behind the Iron Curtain, the men were treated like VIP’s. They were escorted on sight-seeing trips and were the guests of honor at various receptions and events. Even so, the training on the open, choppy Khimki Reservoir was intense. Ulbrickson was also visibly upbeat, seemingly more relaxed. Maybe stroke John Sayre translated the thoughts of his coach when he said “We love that rough water – it felt just like Lake Washington.” (3)

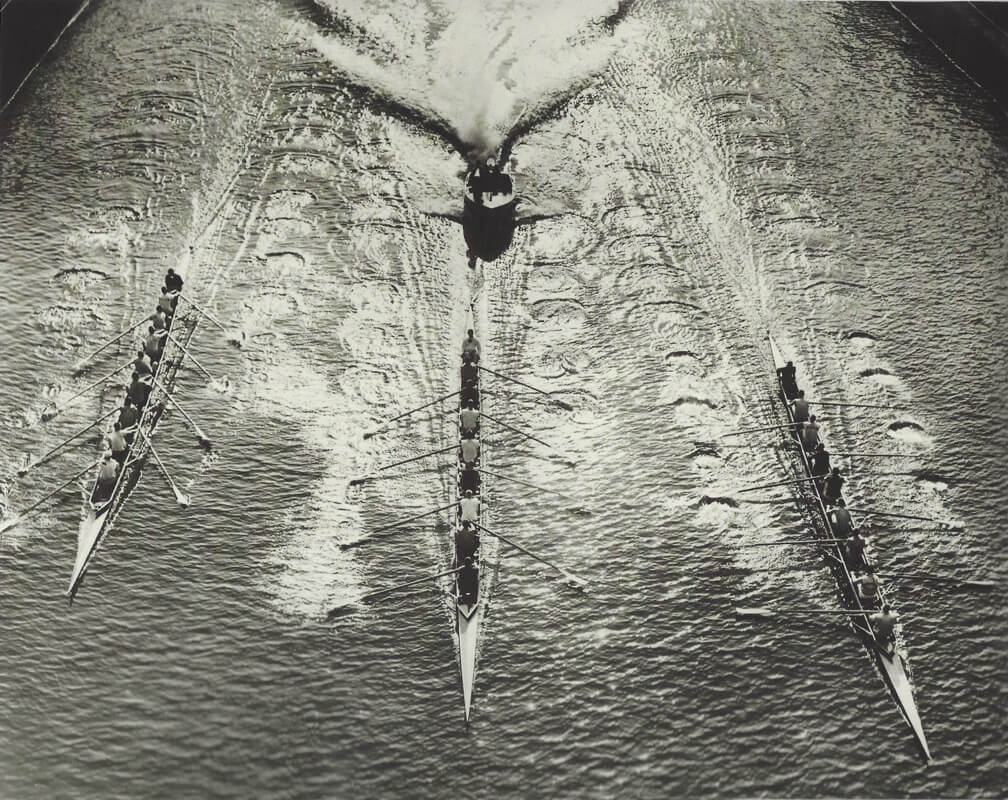

On July 19th, the Huskies lined up against Leningrad Trud – their adversary from Henley – and five other top Russian crews for a 2000 meter race across a wind-blown and choppy Khimki Reservoir course. Into the quartering headwind, the crew got a much cleaner start than at Henley, with the Soviet Army crew and Leningrad only inching out into the lead. Stroking at a thirty-four, Sayre maintained a solid run and the crew began to move out to a lead. By midway, they were up by a half length over Leningrad with the rest falling back. In the final 1000 meters, the Huskies pulled away to win by open water. “The boat was really singing” said Bissett. “The boys rowed it perfect.”

The Soviet crowd cheered the Washington crew with a standing ovation. The team was showered with gifts at a post event function. The men had numerous pictures taken with their hosts. Ulbrickson called the anonymous donor of the Swiftsure to see if it was OK to leave the shell as a gesture of goodwill. It was. He did. It was a “people to people” event that rang true in both countries.

But though the political significance would be left to the politicians to debate, the athletic significance was clear. The victory was a stunning comeback for Washington in many ways: from the defeat at Henley to victory in Moscow; from the depths of a dubious probation to international acclaim. Years later Ulbrickson, explaining why he considered this season the highlight of his career, said “One item made the Moscow race a little more gratifying…we came back from a decisive defeat. No coach could have asked for more.” The athletes that rowed the Swiftsure that day carved their name into the Washington Hall of Fame; inducted in 1984, it was this crew that opened the doors of international competition to all future generations of Washington oarsmen.