Two months later all three crews were back in Poughkeepsie. The freshmen and JV’s both defended their titles, but the varsity remained a question. In opposite fashion of the two years before, this time the crew was almost instantly behind, and settled at a stroke rate below 30 – the leading crews moving out to a multiple – at least five – length lead. There the Huskies remained through the balance of the course, methodically stroking a 28, the crews in front, including California and Navy, sitting on them. At a mile and a half, Washington turned on the power like a switch, raised the stroke to 34, and the shell lifted out of the water. “We took off…we just flew by them” says Bob Moch, almost as surprised today as he was decades ago to feel the unleashed power of this crew. The win completed the first ever sweep of the Poughkeepsie by a west coast crew – and was the first ever varsity win for Ulbrickson.

Moch reflects on a practice at night on the Hudson river with this crew prior to that race, a defining moment for the team. The crew had postponed an afternoon time trial on the course because it was so windy and rough, and had gone to a movie instead. On the water that night after it had calmed, he remembers “it was pitch black, the wind calmed down and after the time trial was over, we turned around and headed for the shellhouse…all three crews were together, we started out, just going 26, 27 – just going home – we got so far ahead of the other two crews we couldn’t even hear them … you couldn’t hear anything… you couldn’t hear anything except the oars going in the water…it’d be a ‘zep’ and that’s all you could hear – the oarlock didn’t even rattle on the release.” A shared moment in rowing history that special crews experience – still to this day.

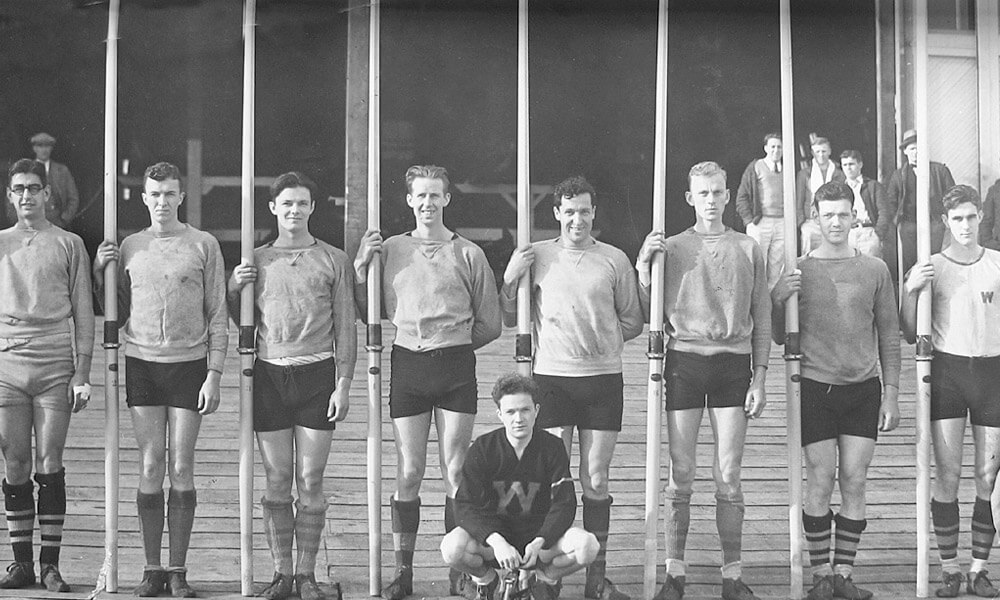

From Poughkeepsie the men traveled to Princeton New Jersey for the Olympic trials. On July 5th they met a polished Pennsylvania Club Crew, New York Club Crew, and Ky Ebright’s California crew for the right to represent the country in the Olympics. Ulbrickson’s now practiced strategy of “Keep the stroke down and then mow ’em down in the finishing sprints” was executed to the letter by his team, casting all three crews out for almost a full length while rowing a 34 before reeling them back in one by one. In the final 400 meters, the Huskies walked through the Pennsylvania crew as Hume took the stroke up to a forty, and they won by a length going away. “Hume stroked a perfect race and I think this crew will give a good account of itself in Berlin” said Ulbrickson.

The men stayed at the New York Athletic Club rowing quarters on Travers Island north of New York – with time for rest and rejuvenation – until departing with the entire Olympic Team for Hamburg aboard the S.S. Manhattan. George Pocock and members of the NYAC helped place the Husky Clipper onto the boat deck of the ship for safe transport to Europe.

Once in Germany, the team stayed near Lake Grunau, the site of the Olympic competition, at Koepenik. The team worked out twice a day on the lake, and dined at night with all of their competitors in the same mess hall. They also participated in the Opening Ceremonies, marching before Hitler and 120,000 frantic German fans, and attended some of the games.

The race format was similar to today. Three heats, with the winner advancing to the final, and a repechage (second chance for those not winning a heat), with the three top places of that race also advancing to the final. Washington won their heat against what Ulbrickson and Pocock felt would be the toughest competition, Great Britain, and in the course of doing it set a new world record. Germany and Italy won the other heats; these three crews now had two days of rest before the final.

And rest was important for Washington. Both Gordon Adam and Don Hume had contracted an illness earlier in the week. The effort during their prelim only exacerbated the symptoms, particularly Hume’s. On the day of the final race, he was plainly ill – but Ulbrickson had made his decision. Much like Rusty Callow and Dow Walling at Poughkeepsie in1923, the alternative was not spoken that day. Hume would race.

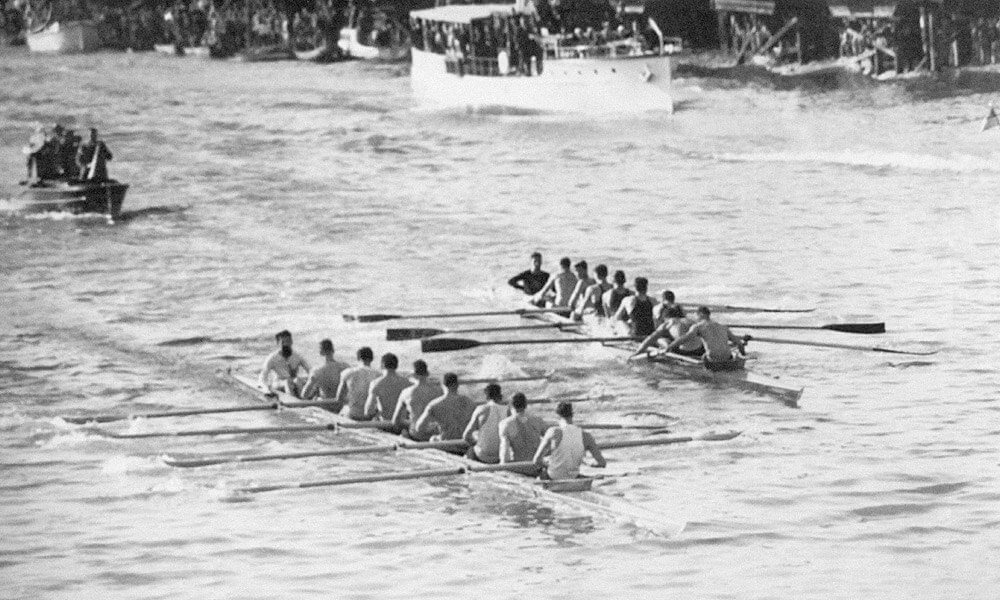

The six crew final was in the afternoon. Washington was assigned lane six, based on the German officials’ decision to position the slowest qualifiers in the most protected lanes (this was challenged by the Americans to no avail). The slowest qualifier was Germany, the second slowest was Italy. The starter faced into the quartering headwind, and his commands were unheard by the Huskies, who nevertheless got a decent start. Hume brought the stroke down to a 36, and the crew went on cruise for the first 1200 meters.

Germany, Italy, and Britain all moved ahead, with the leader, Germany, at least a length up. Fighting the quartering headwind in lane six, the Huskies began to increase the stroke rate. Finally, with about 500 meters left in the race the lakeshore changed, disrupting the lee in which Germany and Italy were racing. The quartering headwind was now evenly felt, at about the instant Hume and his crew began to sprint. By now we know what happens when this crew would sprint, and the confidence they had in each other; every race in 1936 this crew had fallen behind, only to gain it back. The last 200 meters were a blur, with Hume bringing the stroke rate up to an unheard of 44, the crowd chanting “Deutsch-land, Deutsch-land, Deutsch-land”, and yet it was in that last 200 meters that the United States went from third to first, crossing the line about ten feet in front of Italy, with Germany third.

The exhausted crew rowed in front of the grandstand, then to the dock, where a wreath was placed over the head of each oarsman and the coxswain. There were no interviews. The men stayed in their quarters that night. The next day they received their medals in the Olympic stadium; after the games were over, they went home various ways, some choosing to travel Europe, others going straight home.

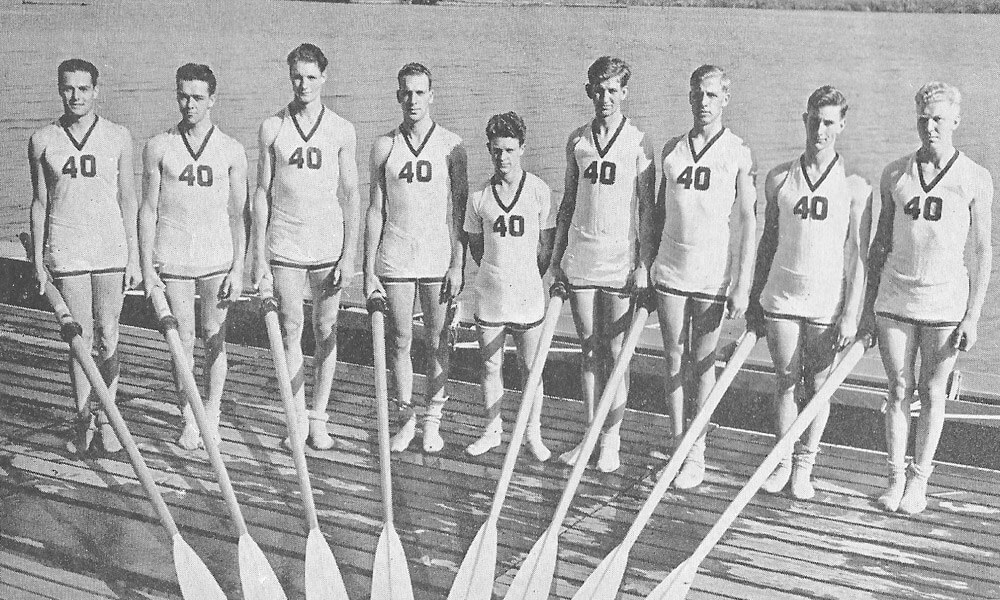

Historically speaking, the 1936 Washington crew would have been memorable without the Olympic victory. By sweeping the Hudson for the first time, the crew established itself as the deepest to date; with the varsity coming from lengths back in the last half mile, it established itself as one of the strongest.

But with the almost surreal Olympic victory in pre-war Germany, the crew became legendary. And although the story itself seems to have a life of it’s own – every perspective is different, and the years blur some of the details – the fact remains that this is the first Husky eight-oared crew to complete their season as undefeated National Champions – and – World and Olympic champions. And forever will they hold that honor.

Events of the Century – is the article from the December 29th, 1999 Seattle Post-Intelligencer naming the 1936 Olympic victory as the greatest Seattle sports moment of the 20th century. Some of the story is a bit embellished – there is no other record of the team ever meeting Hitler – but the story is accurate from the personal perspective of these athletes; after the race they were, for a man, so physically and emotionally exhausted it was likely impossible to remember the race and post-race details a week later – let alone sixty-three years later when this article was written. Although various perspectives may differ – what crew wouldn’t – it certainly catches the electricity of the moment so many years ago.