One of the first orders of business for Coach Conibear was to procure the Coast Guard station and lighthouse, built for the AYE, as new crew headquarters. This building, at the foot of “Pay Streak” – the main amusement corridor linking the upper exhibits to the lower fair – would also be home to the new Varsity Boat Club, established in this year under Conibear as a social organization for all of the upperclassmen who rowed on the team. The building was located on Portage Bay, in fact very near where the west end of the Montlake Cut is today. At the time, of course, there was no Cut, and no access to Lake Washington. The crews practiced in Portage Bay and Lake Union for about six years, carrying the shells over to Lake Washington in the spring. In 1916 the Cut was completed, opening up miles and miles of Lake Washington – much to the joy of Conibear.

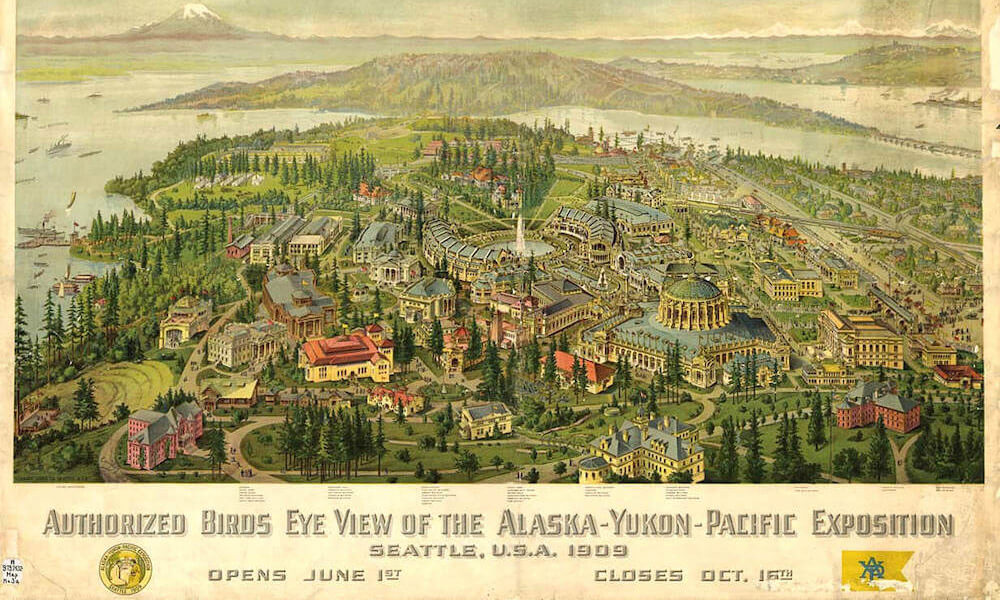

In this map of the Alaska Yukon Exposition, the bay to the left is Union Bay (part of Lake Washington); the bay to the right is Portage Bay (part of Lake Union); and the green, low level area in between is where the Montlake Cut is today. “Pay Streak” runs north to south (down to up) in the middle/right in this picture; the Life Saving Station (future home of the VBC) is the thin white tower at the foot of “Pay Streak” (on the southeast end of Portage Bay) with the large ship anchored out front.

And one final note from the AYE. As part of the cultural celebration of the fair, Igorot Tribesmen – indigenous people of the Philippine mountains – put on a daily show of native dances. It was from that that the team began to reference the freshmen as “igorotes”; although today such a reference would be unthinkable, the evolution of history is important. In fact, it was in the counter-culture revolution of the sixties that the team became uncomfortable with the reference, with the term “gruntie” finally sticking as the term for the frosh team that is invoked today.

Two new shells were also acquired in 1910, named the Helen and the Walter B. The shells were built wider and deeper, specifications for larger men. It was clear what was on Mr. Conibear’s mind, and unlikely that Conibear changed the training regimen much. Once again the crew only raced inter-class prior to their championship race against Stanford (who had defeated California earlier in the year) slated for Wednesday, May 25th, 1910. It is unclear how the men got the shells to Lake Washington for the races – they were probably carried to the old student-built boathouse on Union Bay a week or two in advance, and possibly, in later years, transported by vehicle.

The course off Madison Park on Lake Washington was windy again, and the race postponed from 10:00 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. (one would think by now spectators had grown accustomed to delays). At 1:30 it calmed enough to get a start underway, with Washington pulling out to an early lead. Stanford outweighed Washington by only six to seven pounds as opposed to almost twenty the year before, with even three-year letterman and now stroke Brouse (Bruce) Beck weighing three pounds heavier than the previous year at a bulky 164.

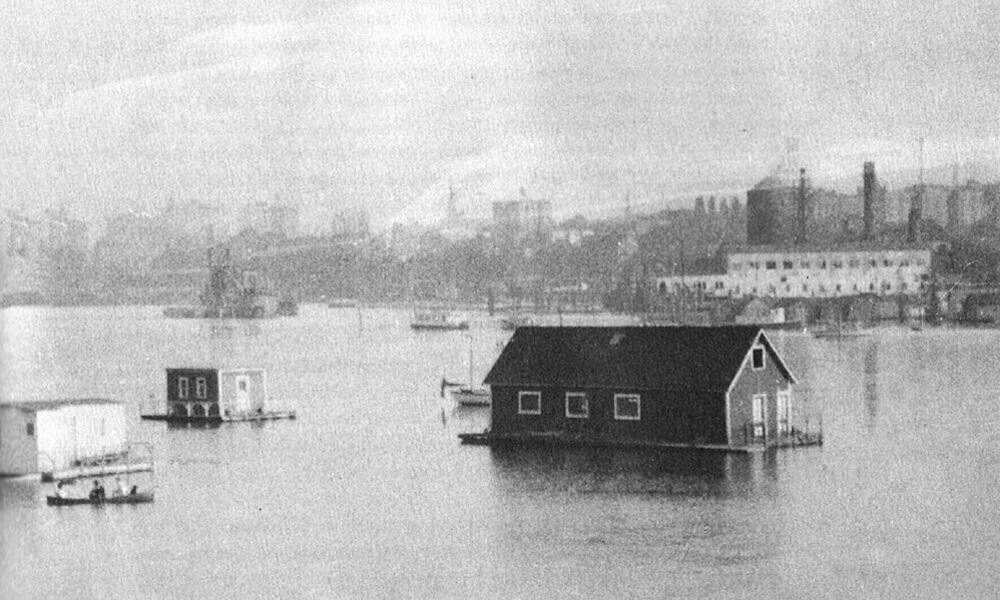

Conibear was also more confident with his new shells, particularly the Helen. Almost immediately however, both crews began to take water over the gunnels. Washington, leading by two lengths as they approached the mile mark, watched as their opponent’s shell dipped and flooded, scattering the crew. Beck tried to quickly drop the stroke rate, but it was only a brief time before the Helen, caught between two large waves and heaving from the weight of the water and men, buckled cleanly in two. The men were sent sprawling. And although all athletes were rescued, the Stanford coxswain narrowly escaped drowning after being trapped under their shell, and was rescued by three followers in a launch.

The race officials gave the race to Washington on account of their lead when the crews went down, but both Beck and Captain Bart Lovejoy refused the declaration, preferring to race again the next day, even though it would mean rowing in the Walter B., a slower, heavier boat unrigged for the Varsity.

The conditions were not much better on Thursday. The race played out similar to the day before: Washington garnering a quick lead, this time Stanford making it halfway through the three mile course before sinking; again Beck lowered the stroke rate, and whether it was because the Walter B. was built like a tank or the waves just not quite as high, the men were able to finish the race in 18:32.

That evening they boarded the Great Northern Railway for a first for the crew team: a trip east of the Rockies to race Wisconsin on June 4th. Two thousand people were reportedly there in Madison to meet the train when it arrived. The race on Lake Mendota was rowed in poor conditions, but Wisconsin pulled away after the first mile and were never seriously challenged, finishing five lengths in front of Washington in 16:06. Even so, the men were proud of their accomplishment, and the fastest time rowed on a three mile course by a Washington crew (16:21).

Conibear, likely a subscriber to the “no publicity is bad publicity” philosophy, knew that the fact the team had even competed against an “eastern” opponent was a milestone in the continued development of his program. However, with the majority of the crew graduating, including a number of three-year lettermen, he also knew that 1911 would challenge his skills as a coach and teacher.